Flicking the switch to electric vehicles

Australia needs to speed up its shift to electric vehicles, Â鶹Éçmadou experts say.

Australia needs to speed up its shift to electric vehicles, Â鶹Éçmadou experts say.

Cecilia Duong

Â鶹Éçmadou News & Content

02 9065 1740

cecilia.duong@unsw.edu.au

Emissions from road transport account for 10 per cent of global emissions – and that number is rising faster than any other sector, as highlighted in the latest report.

This month, governmental delegates from around the world will meet in Glasgow as part of the United Nations’ 26th annual climate change summit, the Conference of the Parties (COP26). Countries are asked to bring ambitious targets to deliver on carbon-reducing initiatives including the switch to electric vehicles (EV).

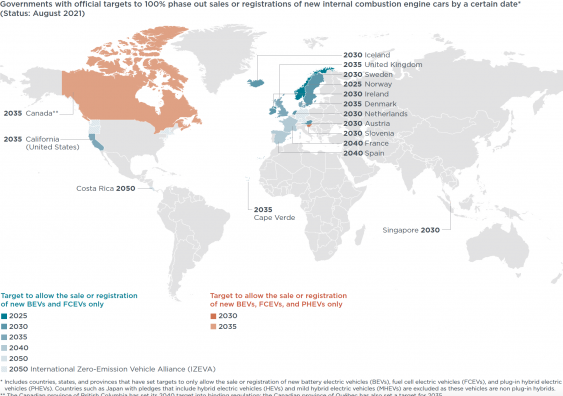

Developed nations around the world, including the United Kingdom and Canada, have already pledged to phase out sales or registrations of new internal combustion engine cars by a - but Australia has not.

Despite being one of the world’s leaders in renewable energy research and innovation, Australia’s vehicle emission standard is still based on the European Emission Standard five, which is now over a decade old. More than 80 per cent of the now follows 'Euro six' vehicle emission standards, including Europe, the United States, Japan, Korea, China, India and Mexico.

Beyond the failure to reduce regional air pollution, Australian standards have also fallen behind in mandating fuel efficiency and hence lowering greenhouse emissions. Cleaner and more fuel efficient internal combustion engine cars can assist in reducing both local air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

So how can Australia commit to zero emission vehicle goals if it’s behind on global vehicle emission standards?

Associate Professor Iain MacGill, Joint Director of Â鶹Éçmadou Collaboration on Energy and Environmental Markets, says despite Australia’s move to support clean electricity initiatives, it hasn’t made a serious effort to address transport related emissions.

“The transport sector is one of the continuing growth areas of Australia's emissions profile,” he says.

“However, we’ve seen so many petrol-fuelled sports utility vehicles and twin cab utes being purchased that it seems likely that the average fuel efficiency of Australian cars is going backwards.

“We are actually making progress on cleaning up electricity, but really struggling with transport emissions, which continue to climb.”

European countries, such as Iceland, Norway and Sweden, have all pledged to phase out the sales or registration of internal combustion engine cars. Image: UKCOP26.ORG

The pathway to zero emission transport almost certainly requires electric vehicles fuelled by zero emission electricity. Last year, less than one per cent of new cars bought in Australia were EVs. That compares with more than four per cent globally, almost six per cent in China and nearly 75 per cent in Norway.

Renewable energy expert, Associate Professor Anna Bruce from Â鶹Éçmadou School of Photovoltaics and Renewable Energy Resources, says the absence of clear Government policy is the biggest reason why Australia is lagging in the transition to EVs - making it difficult for manufacturers to focus on serving the Australian market.

“The catalogue of EVs available to Australian drivers is very limited because we don’t really have a clear policy on it. This discourages car manufacturers from investing in producing left-hand drive versions of vehicles that are already available overseas,” she says.

“It’s also difficult to import second-hand vehicles into the country and on top of that, there are additional road taxes for EV owners. So, it’s roadblocks like these that are impeding the adoption of EVs in Australia.

“It’s like the chicken and egg dilemma – but without proper policy and regulation, then demand for EVs will remain low.”

The same can be said about the network of EV charging infrastructure, says A/Prof. MacGill.

“Why should Australia invest in more charging stations if there are little EV sales? At the same time, why would drivers buy an EV if they’re concerned about the lack of charging stations?” he says.

“Australia’s an interesting mix in that we’re highly urbanised - so we take the view that our car should get us around town for 51 weeks of the year. But for the other week, we might want to drive all the way to another state.

“In most cases, nearly all the charging happens at home anyway but it’s for those special occasions where we need to drive long distances.

“The charging network can satisfy the number of current EVs but if that number were to double overnight, there will be challenges and we’ll need to rollout more infrastructure to support demand.”

Â鶹Éçmadou PhD candidate Katelyn Purnell, whose research thesis explores electric vehicles and electricity grid modelling and planning, says we need to think bigger if Australia wants to meet its Paris Agreement commitments.

“While private vehicles make up a majority of transport use, there is a huge opportunity to electrify the entire transport network including bicycles, taxis and rideshare and even ferries,” she says.

“Cross modality transport is an important factor in reducing emissions because people are moving around differently - so policy discussions shouldn’t be limited to just motor vehicles.”

There’s a lot to learn from how other countries have successfully adopted EVs.

If Australia wants to get serious about reducing emissions from transport, then it needs to start with a cohesive and holistic approach from both the State and Federal Government, says Purnell.

“If we look at Norway, they went with a portfolio method when introducing policy. Beyond initiatives such as reducing upfront capital costs, subsidies, or access to special lanes, they signalled to the market that they were serious about this and there was no going back.”