No, you cannot 'devaccinate' yourself with snake venom kits, bleach or cupping

If what you’re reading seems too good to be true, it probably is.

If what you’re reading seems too good to be true, it probably is.

Claims you can “devaccinate” yourself have been circulating on social media, another example of extreme and dangerous misinformation about COVID vaccines.

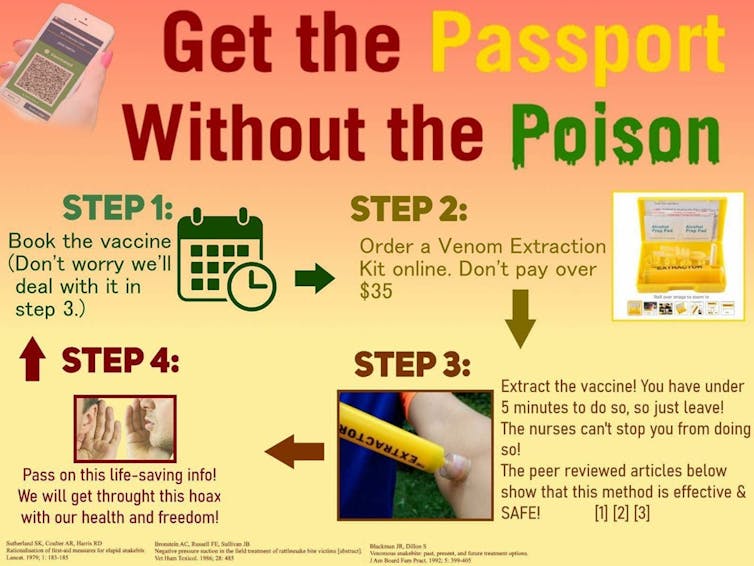

Methods said to remove COVID vaccines from the body include using snake venom extractors or a type of traditional therapy known as “wet cupping”.

If you encounter claims like this online, you need to ask yourself four questions, to figure out whether these claims really are too good to be true.

Misinformation circulating on Instagram and other social media includes a video of someone using cupping therapy, suggesting this removes or sucks out the COVID vaccine.

The video shows someone cutting the skin, before applying a cup over the cuts to create suction – a type of therapy known as “wet cupping”.

Cupping has been used for thousands of years, mostly in traditional Chinese medicine. Practitioners believe this eases pain or promotes healing by drawing fluid towards the treated area and improve the flow of energy. However, there are few high-quality studies to support its effectiveness.

Cupping therapy is said to ease pain or promote healing by drawing fluid towards the treated area.

Cupping usually affects only the superficial layers of the skin. COVID vaccines are generally deeper, .

After injection, vaccines train the body’s immune system to fight SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID. They do this by either presenting a weakened or inactivated part of the virus (the spike protein antigen) to the immune system, or by delivering the instructions for the body to make these antigens.

It’s important to note, this period of “training” is very short, and once the body has learnt how to respond, the vaccines are cleared from your body in mere days or weeks.

That’s because after the vaccine has primed the immune system, the body , just as it does with other genetic fragments, proteins and fats.

Others have tried to devaccinate using venom extraction kits. These kits include a plunger-type device you place over a snakebite, which is supposed to suck out venom.

Again, venom extractors will not remove the antigen in COVID vaccines, for the same reasons we’ve already described.

Venom extractors don’t remove enough snake venom, let alone COVID vaccine (Author supplied).

They also cannot remove enough venom to prevent serious systemic (widespread) effects of a snakebite. found the kit only removed 0.04% of the total load of venom, and ended up just removing body fluid. Critically, they can destroy tissue around the site of the snakebite.

Information about devaccination continues to circulate on some platforms, such as BitChute and Telegram.

If you come across someone selling a wonder cure or drug online – whether that’s related to COVID or some other illness – here are about what you see:

1. Is it hard to believe?

When you see something posted that looks sensational, it is even more important to be sceptical.

In a popular TikTok video, an osteopathic physician, who , suggests people “detox” by take a bath in baking soda, epsom salt and borax to get rid of “radiation, poisons and nanotechnologies”.

She says people need to detox because COVID vaccines have “RNA-Modifying Transhumanism-Nano-Technology”, and “the people pushing these injections want to change what it is to be human”.

She to have identified a jellyfish-like tiny invertebrate called “Hydra Vulgaris” that can:

multiply and form independent neural networks inside those who have received COVID-19 vaccines and could ultimately influence their thoughts and actions.

Now, we have to worry about jellyfish controlling our minds? Photo:Â

Even though sometimes we want to believe that someone has found the cure or answer to a question we are seeking, go with your gut reaction. If it sounds ridiculous, it probably is. If you are unsure whether the information is legitimate, talk to a family member, friend or your GP.

2. Have you checked the facts?

If a resource is provided in another language, how can you be sure what it says?

Using the cupping video as an example, Stephen Dickey, a professor of Slavic languages and literature at the University of Kansas, identified the dialogue in the video as Russian. But he “there was no mention of the vaccine” and “there is no mention at all of exactly what is being extracted”.

When reviewing the resource, do you know who the author is and does that author specialise in the field the article is concerned with? Check LinkedIn or do a quick Google search to see if the author can speak about the subject with authority and accuracy.

3. Is there a hidden agenda?

Have you considered whether the person or organisation attempting to sell you a new drug or treatment has a hidden agenda? This can be increasing their reach on social media or making money.

For example, American “archbishop” are reported to have sold more than of their bleach-type “Miracle Mineral Solution”. They said it was COVID, cancer, Alzheimer’s, diabetes, autism, malaria, hepatitis, Parkinson’s, herpes, HIV/AIDS and other serious medical conditions.

4. What’s the source?

When an article cites sources, it’s good to check them out. The post about the snakebite kit included references to three published papers. These were dated 1979-1992, decades before COVID.

It’s also important to look at the topic of the cited paper. In the case of the 1979 paper, this looked at measures for , which included examining the effects of applying firm crepe bandages on monkeys. There was no mention of the use of snake venom removal kits or COVID.

So, when you come across any videos or social media posts about fantastical new drugs or treatments that promise otherwise impossible cures or outcomes, it is important to :

If what you’re reading seems too good to be true, or too weird, or too reactionary, it probably is.

, Associate professor, and , Paediatrician at the Royal Children's Hospital and Associate Professor and Clinician Scientist, University of Melbourne and MCRI,

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .